Some of the most irritating cases I’ve seen with hardcoded date formatting come from large, well-resourced tech companies that should theoretically know better: Adobe, Apple, PayPal and Google come to mind. I wouldn’t be surprised if Microsoft did similar things, though I use more Adobe, Google and Apple products. As a user of non-US UI region formats and languages, I frequently encounter problems with date and time formatting. The Month/Day/Year format is not portable. It should not be the default. Never default to Month/Day/Year, and never hardcode date formatting. As soon as you localise your software to something other than English (US), it’s backwards. Developers should default to the ISO standard Year/Month/Day format and derive settings from users’ set region format or language, prioritising region format.

Adobe products, both on the web and on the desktop, have a long-standing and pervasive problem with hardcoded US date formats regardless of the language the app or website is set to. I’ve mentioned the problems with Behance, but it’s not limited to that site. The document setup screens on Photoshop, Illustrator and other Adobe applications all display dates in the Month/Day/Year order, even if you’re set to a different language. I use Photoshop and Illustrator in French. The names of the months and days change to French, but the dates are in the wrong order and the 12-hour clock appears. France does not use the twelve-hour clock. A Month/Day/Year date should never appear on any applications on this computer; my UI language is set to French and my region format is a customised one with a Day/Month/Year preference. I’ve brought it to the attention of the Adobe team, but I haven’t seen any changes yet.

On the App Store, Apple thinks that the date and time format of your local store takes precedence over your own region settings if they differ. Everything related to the App Store shows US Month/Day/Year dates, even though my region format is set to UK. The Mac App Store is even weirder. The Available Updates section shows the Month/Day/Year date format, even if you’re logged into a UK account. The correct Day/Month/Year format shows under Purchased and Updated, though. Most Apple apps pick up the correct date format, though. Also, some features in the iWork apps prioritise the UI language over the spellchecker’s language. Just because I have the UI set to French doesn’t mean that I necessarily want dates to appear in French in Numbers, since my spellchecker is set to English. I’ll still take French dates over a date format I didn’t choose though. At least I picked French as my UI language.

Update, 23 August 2018: Apple has improved the way dates appear in both the Mac and iOS App Stores. On the Mac App Store’s update page on the Mojave beta, the user’s region format now takes precedence over the user’s local store settings. The Updates section of the Mac App Store now shows the Day Month Year date format for me, even though I’m logged into a US account. Before, it forced the Month Day, Year format regardless of what my actual settings were. Since iOS 11, the app update section has respected the user’s region format. Unfortunately, review pages on individual apps still default to the local store’s settings.

PayPal’s settings are just as asinine as Apple’s. Because of my account location, I’m still treated to Month/Day/Year dates and the 12-hour clock, despite my phone being set to display Day/Month/Year dates and a 24-hour clock. I tweeted PayPal support about the app overriding my settings. The representative told me that date and time settings are based on your account location, not your phone or computer settings. This is silly. How difficult is it to respect a user’s settings? iOS and Android make it possible for apps to detect date formatting using their own protocols.

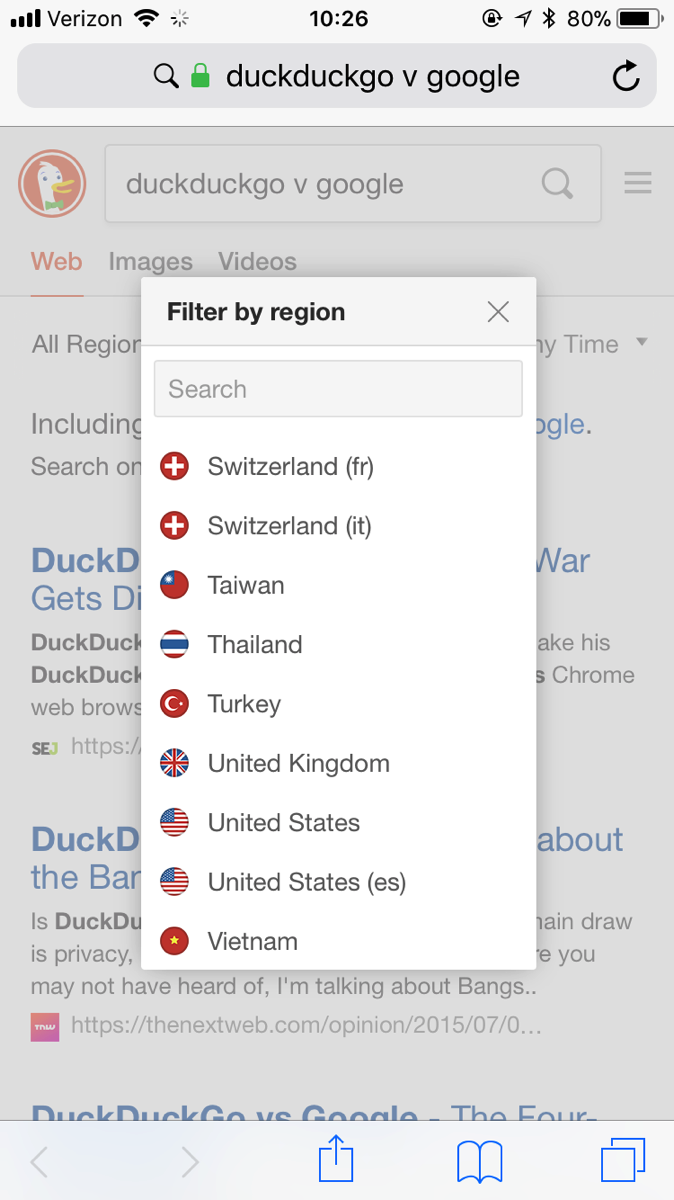

Date formatting in Google search is dependent on the region they’ve detected for your search results. Before they changed all the top-level domains (google.com, google.co.uk, google.de, etc) to deliver local results based on your detected IP address, the site you chose determined your date format. I’ve been using google.co.uk for years because it shows dates in the sensible Day/Month/Year format. When I noticed Month/Day/Year formatting on google.co.uk, I wondered what was going on, since it contradicted my language settings. I found out that I had to go into search settings to switch my results to UK in order to bring back my date formatting preferences. This makes it harder for me to get local results. Why can’t I get local results and have my language and date/time format preferences? Other Google products, like Docs, Gmail and YouTube, correctly use language and dialect, not physical location or regional result settings, to determine date formatting.